Young children have become an increasingly important audience for museums around the world. While many cultural institutions offer something for children, approaches and practices towards this audience vary dramatically across the sector.

In this post, early childhood and museum education specialist Sharon Shaffer shares her top tips for connecting young children with museum objects. Sharon was Director of the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Centre (SEEC) for 24 years. The SEEC is a lab school in Washington D.C. with a museum-based curriculum. Children attending the Centre visit and learn in the various Smithsonian museums every day.

The post begins with Sharon telling us a little bit about her background in museums and education. The two of us then discuss topics such as the importance of scaffolding in children’s learning, how learning can be evaluated in museums and the need for flexibility in the design of early year’s education activities.

Sharon’s background in early year’s museum education

Education has always been my passion. Children’s learning and the opportunities that museums and collections offer is at the heart of my work as an educator, a passion that began in 1988 when the Smithsonian Institution asked me to establish a national model in museum-based education for young children. Our lab school, the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Centre, introduced young children – infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and kindergartners – to the treasures of museums and engaged them in understanding their world through cultural artefacts, scientific specimens, and works of art. Our experimentation with age-appropriate strategies served as the foundation for the program and later, our training programs offered to educators around the world.

Beyond my leadership of the Smithsonian’s model, I consulted with museums and schools across the United States and abroad, and after nearly 25 years at the Smithsonian, I ventured into independent consulting in 2012. My work today includes an appointment as a senior advisor for the Children’s Museum Research Center (CMRC) at Beijing Normal University (China) as well as short-term consulting for various museums and institutions such as the Barnes Foundation (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and the High Museum of Art (Atlanta, Georgia) as examples.

As an author, I’ve recently dedicated time to professional writing, focusing on children and museums. My first book, Engaging Young Children in Museums (2015), offers a balance of theory and practice for museum educators, providing important background knowledge that includes the history of children in museums and educational theory as well as a real-world application for the practitioner. My new book, Object Lessons and Early Learning (Routledge, July 2018), offers a focused perspective on the role of the object in learning and examines how children learn from interaction with objects that range from everyday objects of the world to treasured artefacts, natural specimens, or artworks.

Louisa Penfold: I am really interested in how museum objects can be used to facilitate children’s learning. Different education theories, such as constructivism and social constructivism, talk about children’s learning with objects and materials differently. What are the key education theories that you draw on in your books and how can these be used to think about children’s learning with museum objects?

Sharon Shaffer: Engaging Young Children in Museums recognizes a constructivist approach to learning as a foundational theory. I write broadly about constructivism, the notion that individuals construct knowledge internally based on a range of factors such as prior knowledge, interests, cultural beliefs, and interactions with the environment and acknowledge the theories of Dewey, Vygotsky, Piaget, Bruner, and Gardner as some of the core contributors to the idea of constructivism. Knowledge is unique to the individual and constantly in flux, changing with experience. Social constructivism, as described by Vygotsky, suggests that all learning is socially mediated. So while I speak broadly of constructivism and think that objects and the environment contribute to meaning-making, social interactions are essential to learning. To a certain extent, I think about social constructivism as an element of constructivist learning theory.

As an educator, one of the most critical ideas that every educator should consider is Vygotsky’s notion of scaffolding as a means of supporting learning and the associated idea coined “the zone of proximal development.” This theory suggests that learning has a baseline where a child succeeds in tasks independently as well as an upper limit where regardless of support or facilitation, a child is incapable of success. The key to good practice for educators is challenging the child in that space or zone in between defined boundaries and supporting achievement through facilitation. Experience is central to constructivist theory and should be understood to include both social interaction and encounters with objects as essential to the learning process.

LP: When I visited the SEEC back in 2012, I was so impressed by how the lab school brought together the Smithsonian museum’s collections with children’s interests. Are there any key principles that museum educators could take from the SEEC’s curriculum to design museum education programs?

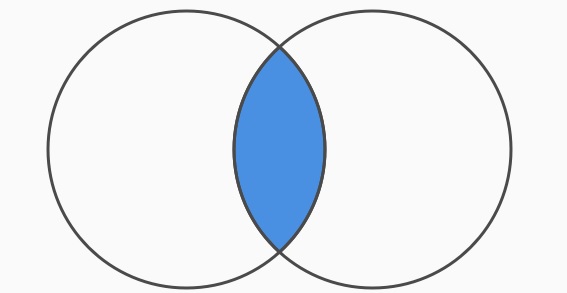

SS: SEEC’s Museum Magic is one valuable source for curriculum ideas coupled with the imaginative and creative ideas of teachers and was most important in SEEC’s early history as the program was developing. The concept essential to “bringing together museum collections with children’s interests” is something that I think about as relevance. The idea is to bring together the child’s prior knowledge stemming from experience with new ideas related to a museum’s collections or the introduction of any new concept. Think about two intersecting circles, one representing the child’s knowledge and the other representing the museum experiences and collections. That place of intersection (the shaded space) is the sweet spot where learning is most likely to happen and memories will be strongest. Educational theory and research both suggest that building on prior knowledge is critical to learning.

Therefore, knowing your audience and understanding the types of experiences they’ve had as well as expressed interests is the starting point for building a museum experience. It might take a little creativity to find that intersection with an object in the collection, but most times it’s possible. For example, an African headrest (pictured below) is an unfamiliar artefact for most children, but almost every child has some experience with a pillow used for resting. Making connections between tangible objects and children’s interests link the unfamiliar with the familiar.

LP: Do you have any advice for practitioners on how to evaluate young children’s learning in museums?

SS: Evaluation of young children’s learning is an interesting topic and often perplexing. Evaluating children that are in your class allows for some different techniques that aren’t possible for museum programs where children visit for a brief time. Within a classroom, educators can listen closely and document conversations of children to understand if and how new words and concepts are integrated into conversations in play or with peers. An excellent evaluation tool is drawing, where children provide insight into their museum experience, memories or knowledge, by drawing their impressions based on a guiding question. For example, “If you returned to the museum with a friend, which objects or exhibitions would you want to include in your experience?” Draw those objects or exhibits. When the drawings are complete, ask each child to dictate remarks about their drawing. Evaluation is important. We need to think specifically about the questions to make sure they reflect what we hope to learn.

LP: What do you think is the biggest challenge for museum educators developing early childhood programs? How could this be resolved?

SS: There are a variety of challenges for educators interested in developing early learning programs, but one that is often frustrating is the lack of knowledge about learning in the early years and the impact that rich, sensory experiences can have on a child’s development. There are still too many individuals, some in positions of power in museums, who continue to see young children through the lens I describe as the innocence of childhood rather than to open their minds to current research and models of excellence supporting early learning. Passionate educators in the field are striving for universal understanding and acceptance of young museum visitors, but achieving that goal is still in the future.

In practice, I think it’s important to recognize the need for flexibility when planning for children’s programs. The established plan may shift as the children’s ideas are brought into play. Listening to children and incorporating their interests and thoughts into the experience makes it meaningful rather than prescriptive. Remember that engaging children requires authentic conversation where children are able to express their curiosities and explore. Incorporating some element of choice into programs offers a range of experiences that honours and respects children’s interests and differences. Our goal should be meaningful engagement!

Sharon’s book ‘Engaging Young Children in Museums’ is out now through Routledge. Her forthcoming book ‘Object Lessons and Early Learning’ will be released in July 2018.