This post is coming to you from sunny California! I absolutely love this part of the world. Yesterday I visited the very fun ‘Noguchi Playscapes’ exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). The exhibition explores the sculptural playscapes of Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988). In this post, I talk about some of the key ideas and artworks from the show including the role of public sculpture in bringing creativity to children’s everyday lives.

©The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York / ARS

“The playground, instead of telling the child what to do (swing here, climb there), becomes a place for endless exploration, of endless opportunity for changing play” Isamu Noguchi

“Everything is sculpture. Any material, any idea without hindrance born into space, I consider sculpture” Isamu Noguchi

Isamu Noguchi wanted to create public spaces that sparked people’s imaginations. He had a lifelong interest in children’s play and how this could allow them to creatively engage with spaces.

The exhibition ‘Noguchi Playscapes’ takes a fresh look at the work of the pioneering artist and landscape architect. It features a beautiful array of Noguchi’s designs, sketches, models and archival images that he made while designing playgrounds, or what he referred to these as ‘sculptural playscapes.’ These colourful, quirky and wacky sculptures illustrate Noguchi’s ‘vision for new experiences of art, education, and humanity through play’ (SFMOMA website, 2017).

Noguchi was fascinated with the role of sculpture in the urban landscape. He believed that fine art could be brought into people’s every day lives through the design of playgrounds and “play sculptures” that encouraged individuals to learn through physical play (Larrivee, 2011). His playscapes aimed to bring together the powerful combination of aesthetics, functionality and human’s ability to play.

Children’s creative interactions in the playscapes

Noguchi designed his outdoor playgrounds so that they “encouraged creative interaction as a way of learning” (Noguchi Playscapes, 2017). The postwar social and political context that the artworks were created in called for new thinking around how children could be involved in the development of democratic communities. Noguchi believed that that children’s play in public spaces could support their active participation in society (Garcia & Larrivee, 2016).

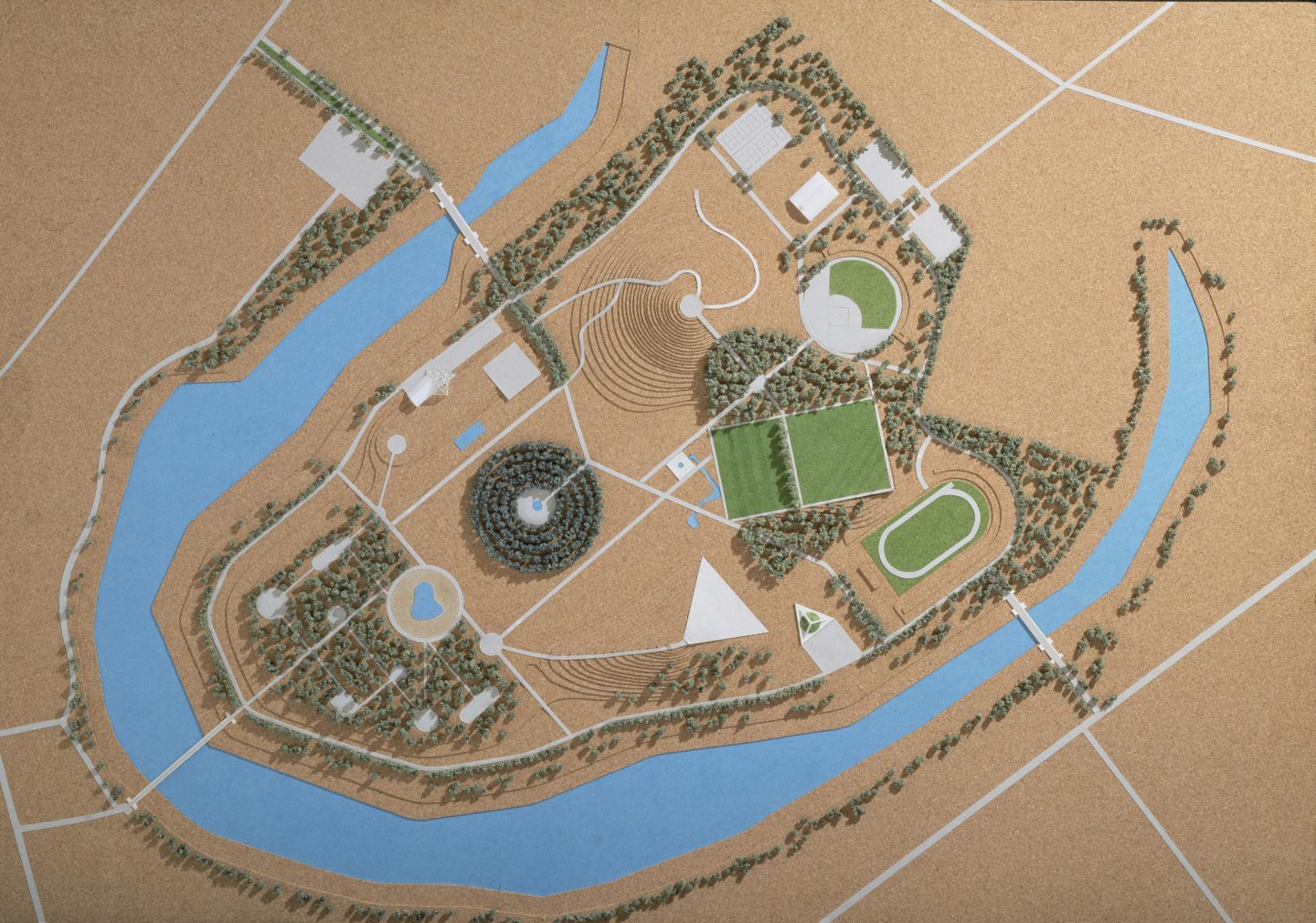

An example of this could be seen in the playscape Noguchi designed from the “The U.S Pavilion Expo” (1970). The design featured huge mounds of soil that had been shaped in unusual ways alongside quirky man-made sculptural equipment. I found the most interesting works in the show to be the playscapes that featured only organic forms such as soil and grass, such as ‘Play Mountain’ (1933). This particular playscape was designed so that children were able to play in the space by rolling, jumping, climbing and sliding down the molded earth. A very different play experience to going on a swing or a see-saw! ‘Play Mountain’ was apparently quite a radical proposition for a playground in 1930’s New York as nearly all the other playgrounds featured mass-constructed, pre-designed equipment. The design was unsurprisingly rejected by New York Parks Commission and never realised into an actual playscape.

After many battles with the government councils to actually build his playscapes, Noguchi stopped designing them in the late 1930’s and then chose to work the rest of his career on private commissions. These collaborations included pieces with architects, musicians, and theatre designers (including this set design for the Martha Graham Dance Company) as a way of escaping the restrictive health and safety regulations of creating public play spaces.

I was surprised to discover that only two of Noguchi’s public playscapes were actually created in his lifetime. One was in Kodomo No Kuni park in Yokohama. Apparently, this was then torn down one year after it was built. The second playground was in Piedmont Park in Atlanta, Georgia (pictured below). Out of all the wacky models and sketches of playscapes featured in the exhibition, Piedmont Park seems one of the simplest and least extravagant. Perhaps it was also one of the more straightforward and most risk-free design to build.

Noguchi Playscapes was on display at SFMOMA from July 15 – November 26, 2017.

Cool links

An article the New York Times wrote about Noguchi’s life after his death in 1988.

If you would like to see more of this amazing artist’s work, you can also visit The Noguchi Museum at Long Island City, New York.

References

Garcia, M & Larrivee, S (2016). Isamu Noguchi: Playscapes, RM/Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo; Bilingual edition.

Larrivee, S (2011). ‘Playscapes: Isamu Noguchi’s Designs for Play,’Public Art Dialogue, 1:01, pp. 53-80.

Noguchi, I (1967). A Sculptor’s World. Tokyo: Thomas and Hudson. pp.176-177.

Noguchi Playscapes (2017), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, July 15 – November 26, 2017.

SFMOMA website (2017). ‘Noguchi’s Playscapes,’ SFMOMA website. Viewed August 14, 2017.

Related posts

Thinking with your hands: A visit to the Tinkering Studio at the Exploratorium in San Francisco

‘Play Time’ at the Peabody Essex Museum

Palle Nielsen, The Model & Play as Social Activism

What are the possibilities of artworks in children’s learning?

The original version of this post was published on this website on August 17, 2017.