This post features an interview with Trevor Smith, curator of the Present Tense at Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. Trevor is also curator of the museum’s current PlayTime exhibition. In our conversation, Trevor discusses the dynamic role of play in contemporary art and culture – a core theme driving the show.

Play and artistic practice have a long and enduring history from Surrealist games that aimed to unlock subconscious creativity to more recent participatory live art practices. Play can be understood as a significant catalyst for artistic, social, cultural and technological change. The Peabody Essex Museum takes this rich conceptualization as a starting point for their PlayTime exhibition. The show features nearly forty works from renowned contemporary artists such as Lara Favaretto, Martin Creed, Teppei Kaneuji and Nick Cave. The museum has also put together a FANTASTIC PlayTime digital publication that is free to access online at playtime.pem.org. The publication includes contributions from distinguished artists, poets, writers and gamers who share ideas around contemporary art and play. Content includes interviews with artists, a list of play-based games for adults and a photo essay by photographer Walker Pickering. I particularly enjoyed the essay, ‘play is in our DNA’ by curator Lydia Gordon. The digital publication is well worth checking out, especially if you are unable to visit PlayTime in person.

Louisa Penfold: I love the connection PlayTime makes between play, creativity and artistic inquiry. When I was reading the exhibition manifesto, that ‘play spurs productivity, play is a catalyst for creativity, play is an escape from conformity…,’ I found it really powerful in how it situated play as a critical force in innovation, productivity, contemporary art and social change. I am really interested in the exhibition’s timeliness and why these ideas are so significant right now. Would you be able to talk a little bit about this?

Trevor Smith: Play has long inspired artistic innovation, particularly at the avant-garde end of the modernist spectrum, but you are right that something is changing dramatically. We have a fundamentally different relationship to play than our parents did—and for several reasons.

There is a dramatic erosion of the modern boundaries between work and play—in which play was merely a reward for a job well done. Today, we carry around these digital devices with us and the boundaries between work and leisure are significantly blurred. Science, like technology, has also advanced and we’re beginning to see how play is indeed at the root of productivity, creativity, and innovation.

Gaming is now a much bigger industry than the movies. The impact of gaming changes how we tell stories. It amplifies the desire to participate in—not just receive—culture. Through this, gaming provides some measure of empowerment and control at a time when we may be feeling a sense of precariousness around the speed of social and economic transformation.

This sense of precariousness is what is driving the urgency of play in contemporary art and culture. Play is the most important tool we have as human beings to negotiate and manage uncertainty. Play allows us to explore our options, test hypotheticals, make up new rules of behavior, and so on.

LP: Play sometimes has connotations to childhood and frivolous behavior. From what I understand, the exhibition explores play as something much more serious through positioning it as a fundamental part of progression and personal empowerment. Can you give an example of an artwork or artist’s practice that explores this idea?

TS: Play is fundamentally about empowerment. When a child turns a tablecloth into a tent or a piece of paper into a hat, they’re testing the physical properties of the world around them, exploring how objects might be used, and negotiating relationships with one another.

I believe this need never goes away because the world is always changing. Yet as we grow up, playing takes on a negative connection. I think that this is a holdover from the strict division that had been set up between work and leisure in the modern era—and is now dissolving rapidly in many areas of culture. Play is seen by some as frivolous because it is thought of as a refusal of productivity and responsibility rather than it being fundamental to it. Play reminds us that rules are not always immutable and that sometimes you can make up new rules as we go along.

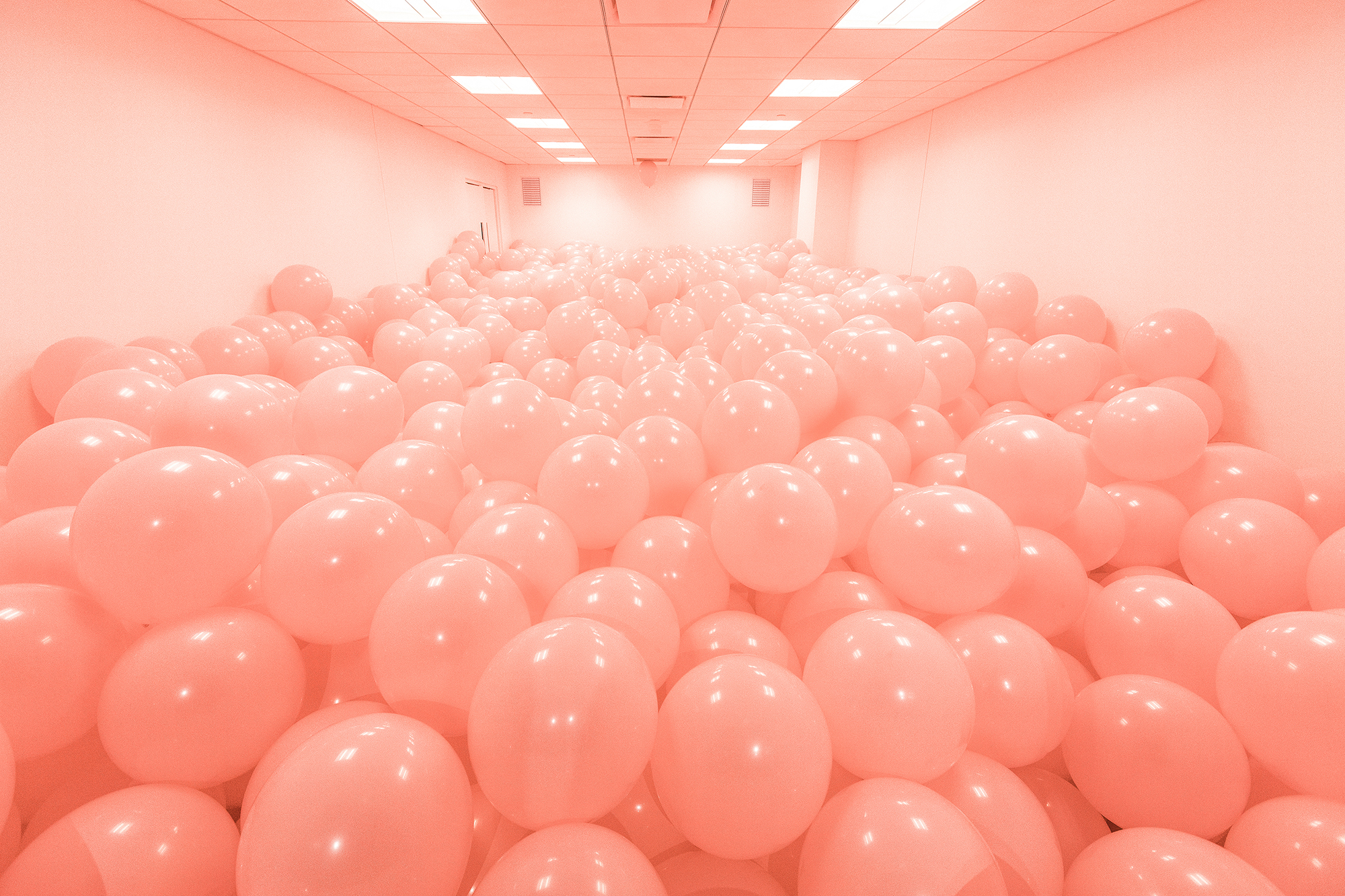

One of the threads that runs through the show is artists who take off-the-shelf objects that are made with a singular purpose in mind and make up new rules for their use. Erwin Wurm invites pairs of visitors to wear a single sweater at the same time. Lara Favaretto turns carwash brushes into a colorful mechanical ballet. Pedro Reyes transforms weapons into musical instruments. Other artists in PlayTime explore the use of avatars—in effect an extension of the childhood game of dress-up. Angela Washko’s installation consists of recordings of performances and discussions she held inside of World of Warcraft. Paul McCarthy offers a viscerally charged re-reading of Disney’s Pinocchio. In terms of play and empowerment, the show begins with works that initially invoke a kind of wonder. Martin Creed’s room exactly half full of pink balloons and Lara Favaretto’s carwash brushes begin the exhibition and visitors are led toward works, like those of Pedro Reyes and Angela Washko, that explore adult conundrums and social complexities more overtly.

LP: The PlayTime website is impressive in how it brings together so many diverse ideas around play and contemporary art. What was the intention of creating such a rich website to accompany the exhibition?

TS: We created the exhibition and the playtime.pem.org digital expression as co-equal partners in a larger project called PlayTime. We certainly didn’t want to make a website that focused strictly on contemporary art. We had a larger story in mind and the desire to explore our dramatically changing relationship to play was the fundamental driver for exhibition and digital platform alike. Online, we were able to explore a much broader array of creative and critical expressions from different “players”—the curators, artists, game designers, poets, comic artists, neuroscientists, visitors, players “on the street,” and more. This expanded field is important to us at PEM. We see ourselves as a museum that is engaged with helping people explore the role of creativity in their lives. Having a subject that lent itself to wide-ranging conversation also facilitated the creative involvement of many museum staff across departments as well as outside partners.

A second factor related to audience development. When museums take on complex, idea-based exhibitions, it takes a while for a discussion to emerge. Our audiences are often ready to have a conversation around the time we are packing up the show and we’re on to the next project. When we launched in September of last year, we wanted the site to offer a conceptual on ramp for our visitors by starting the conversation well in advance of the exhibition opening. We also wanted to capture our thoughts and process through the run of the show and take advantage of the potential for real-time interaction through game play, video dispatches from the field, rapid commissions, social media interaction, and so forth.

Working digitally has also allowed us to engage a much more dispersed audience than the exhibition itself could ever see. It was important for us to reach people who wouldn’t necessarily buy or read exhibition catalogues or who were necessarily conversant with contemporary art per se. So the content of the platform is designed to be able to be broadly accessible, serialized where (you could read a short piece on your phone between subway stops, for example), and diverse in expression, subject, and mood. The commissioned works continue to reach people. This April, designer Jane Friedhoff’s game Lost Wage Rampage will be a part of Now Play This at Somerset House.

LP: How have visitors responded to the artworks in the show? Have there been any playful surprises or responses?

TS: We designed the show to take the viewer through an arc of experience—from child-like wonder to adult complexities. I am delighted at how many people seemed to sense the darkness in the seemingly more innocent works and the joy in the more obviously unsettling pieces.

The work that surprised me the most is a wonderful work by Rivane Neuenschwander who created a version of magnetic poetry using a felted pinboard and specially printed clothing labels. Each label was printed with a word taken from a jpeg of a protest sign that she had collected online. In effect, they were words that protesters had used to empower themselves by giving public voice to their opinions. Visitors are invited to arrange these labels into poems or statements and can also pin them to their clothing and wear them out into the street. By the first weekend of the show, the board (which is about 3.5 meters long) was already completely full. Rarely a day goes by when I don’t see someone walking in the street pinned with Neuenschwander’s words. I think it speaks to the importance people place on play and giving voice, even when the answers are not so clear.

For more Art Play Children Learning posts on play and contemporary art, head over here!

1 Comment

Very cool and interesting work. I would be especially interested in seeing how the printed clothing labels from protest signs turned out.