Documenting children’s learning is an intricate process. In this expert interview, Mara Krechevsky, a senior researcher at Harvard’s Project Zero research centre, discusses the ins-and-outs of making learning visible.

Documenting children’s learning is a complex and (sometimes) confusing process. Questions of how educators can use documenting to support learning are deeply intertwined with debates surrounding ethical and political assumptions in education.

Mara Krechevsky has over 30 years’ experience in education research with a specific interest in documenting learning. In her role at Harvard, she has worked on a myriad of ‘visible learning’ projects including directing Project Zero’s Making Learning Visible, an initiative that began as a collaboration with educators from Reggio Emilia.

Project Zero is a research centre at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. Founded by philosopher Nelson Goodman in 1967, Project Zero began with a focus on understanding learning in and through the arts. Since then, the centre’s mission has expanded to include understanding and enhancing thinking, learning, and creativity in the arts and other disciplines, for individuals and institutions.

Mara has also co-authored two books that address documentation: Visible Leaners: Promoting Reggio-Inspired Approaches in All Schools and Making Learning Visible: Children as Individual and Group Learners. In this post, Mara touches on topics such as:

- What does it mean to ‘document learning?’

- Why is documenting important in education?

- How can documenting be used in education contexts shaped by pre-set curriculum and standardised testing?

Louisa Penfold: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk today. Like you, I am interested in the process of documenting learning and how this can support children’s creative education. It would be lovely to hear you talk about this process at a fundamental level: what does it mean to document learning and why is this important in education?

Mara Krechevsky: I am really excited to talk about this today too. Documenting is a complex construct and concept that I am sure I will always be learning more about. Based on an initial collaboration with Reggio Emilia educators, and then work with kindergarten, primary and secondary educators in the United States, the Project Zero research team spent 10 years coming up with a definition of documentation!

To give you a bit of background, Nelson Goodman who is the founder of Harvard Project Zero, used to talk about the languages of art. He used to say that the question is not what is art but when is art. That is, there is not a fixed definition of art, but rather, the definition of art depends on the context and the presence of certain aesthetic qualities or “symptoms.” Likewise, whether or not an artefact can be considered documentation depends on the context and how it is being used.

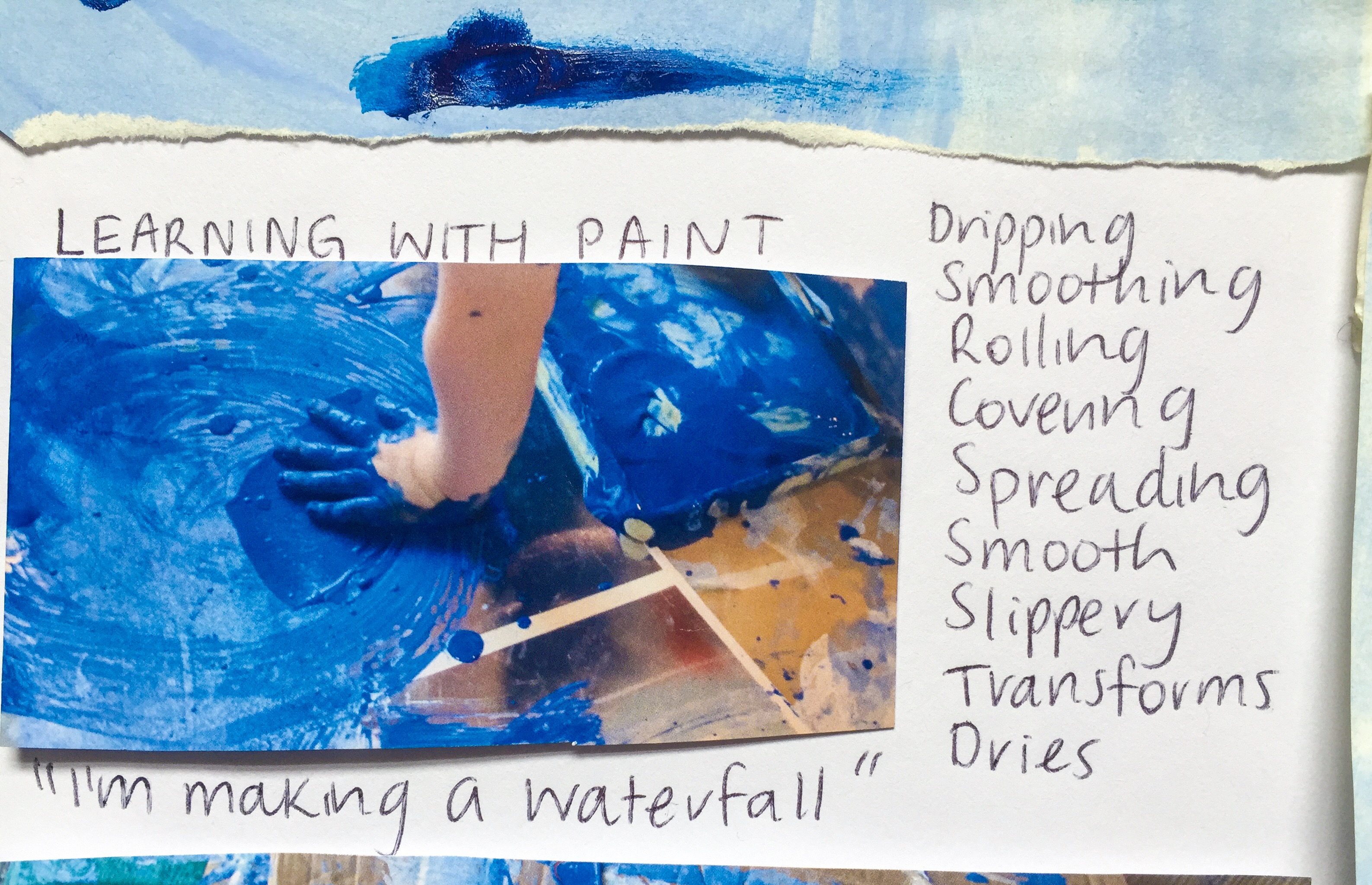

We define documentation as the practise of observing, recording, interpreting (either on one’s own or, ideally, in a group), and sharing through different media the processes and products of learning in order to deepen learning.

One thing we are doing in this definition is making the claim that you do not need to wait until the learning process is over—and there is a final product or an exam score—in order to know that learning is taking place. Rather, you can see learning happening during the process itself. Documentation is one way to make this learning visible, which can also inform future learning.

When we ask people to share their own working definition of documentation, and then compare it to our definition, they often realize they have neglected to mention the “why” of documentation—“in order to deepen learning.” Sometimes, documentation is confused with display, but one difference between documentation and display is that display focuses on what you did, whereas documentation focuses on what was learned. Sometimes people get so engrossed in “learning how to document,” that they forget about “documenting to learn.” So questions we often ask the teachers with whom we work is: What do you want to learn from this documentation? Whose learning do you want to support? Is it the students’ learning, their own learning, the learning of others (colleagues, parents, or other stakeholders), or some combination?

My colleague, Ben Mardell, says that you should only collect enough documentation as you have time to revisit. Howard Gardner talks about documentation as “paring down.” You can’t document everything, so the practice of documentation forces you to become clearer about your educational values and priorities. What is the learning that you care about most? Your answer will help guide your collection and sharpen your analysis or interpretation of the documentation.

LP: Great, ok. My next question is around the age-old debate of ‘how can documenting learning be used in education contexts shaped by pre-set curriculum and standardised testing?’ How can we use documenting to re-think the idea of educational accountability?

MK: Some years ago, I co-wrote a paper on thinking about accountability in three realms. I think documentation can serve three forms of accountability. The first realm is accountability to self—becoming clearer about your learning goals, and then looking at what you intended to teach in relation to what actually happened with the learners in front of you. Documentation helps teachers both become more intentional and more reflective in their teaching.

The second realm is accountability to each other–contributing to the knowledge of others as well as one’s own. Documentation can play a key role in supporting individual as well as group learning, and helping schools to build a collective identity as “a community that learns.” Bringing attention to sharing learning with others encourages learners to take a metacognitive stance and likely deepens the learners’ own understanding as well. It also reinforces the idea that learning is a social process.

The third realm is accountability to the larger community–evaluating the relationship between the school’s mission and classroom practice and student learning. Accountability to the larger community should include multiple ways of demonstrating student learning.

Documentation can provide evidence of valued student learning that is often not assessed by standardized tests.

I am talking about learning like students using their imaginations, thinking critically, listening to and learning from each other, and developing a sense of aesthetics or emotional understanding.

LP: Documenting learning is a topic that has been written about extensively in early childhood education. Do you think this is a process that could be used in other education settings such as secondary schools, museums or community centres?

MK: Absolutely. The book, Visible Learners, shares the results of our work on the Making Learning Visible Project, a multi-year collaboration with teachers in the U.S. from early childhood through secondary school, as well as teacher educators. Documentation has many different meanings; it can take multiple forms and serve different purposes and audiences. If you think about documentation as a way to ground reflection about learning in concrete artifacts of that learning, which others can also point to and make sense of—that kind of “value added” to the reflection process can occur in any of the settings you mention.

Documentation is sometimes referred to as a kind of “visible listening,” or providing a “memory” for a group, or a record of an individual or group’s thinking. All of these meanings have relevance across educational contexts, if adults want to understand what is going on at a deeper level in order to inform future pathways, or provide continuity across learning experiences, or make selected insights, beliefs, or questions visible, so they can be returned to over and over again.

Documentation can also be seen as a political act because it makes a statement about the kinds of learning we value and the importance of understanding other minds. Carlina Rinaldi from Reggio Emilia talks about documentation as an act of love because it helps you to get to know and develop a relationship with the children and adults in your community. I wonder which one of us has ever considered a standardized test to be an act of love!

LP: Are there any final comments or tips you would like to give to educators documenting children’s learning?

MK: I think it is really important to remember that documentation is not an end in itself. This is where the question of ‘What do I want to learn through collecting my documentation?’ becomes really important. Your response to that question will help guide you in knowing what to do with the documentation once you have it—e.g., sharing it back with the learners, asking colleagues to help you interpret a student’s thinking, or shaping the documentation to share more widely in order to provoke people’s assumptions and beleifs about what children are capable of. And I can’t stress enough that in the school context, it is crucial that administrators give teachers the time to meet and to reflect on documentation with colleagues. As Rinaldi says, “this is how we learn to teach.”

Further links

Harvard Project Zero runs a paid online course on Making Learning Visible.

If you would like to read more about making learning visible check out these posts on education apps for documenting learning, documenting learning books and my reflections on a visit to the Reggio Australia pedagogical documentation centre.