‘We play because we are human, and we need to understand what makes us human, not in an evolutionary or cognitive way but in a humanistic way. Play is the force that pulls us together.’ Miguel Sicart

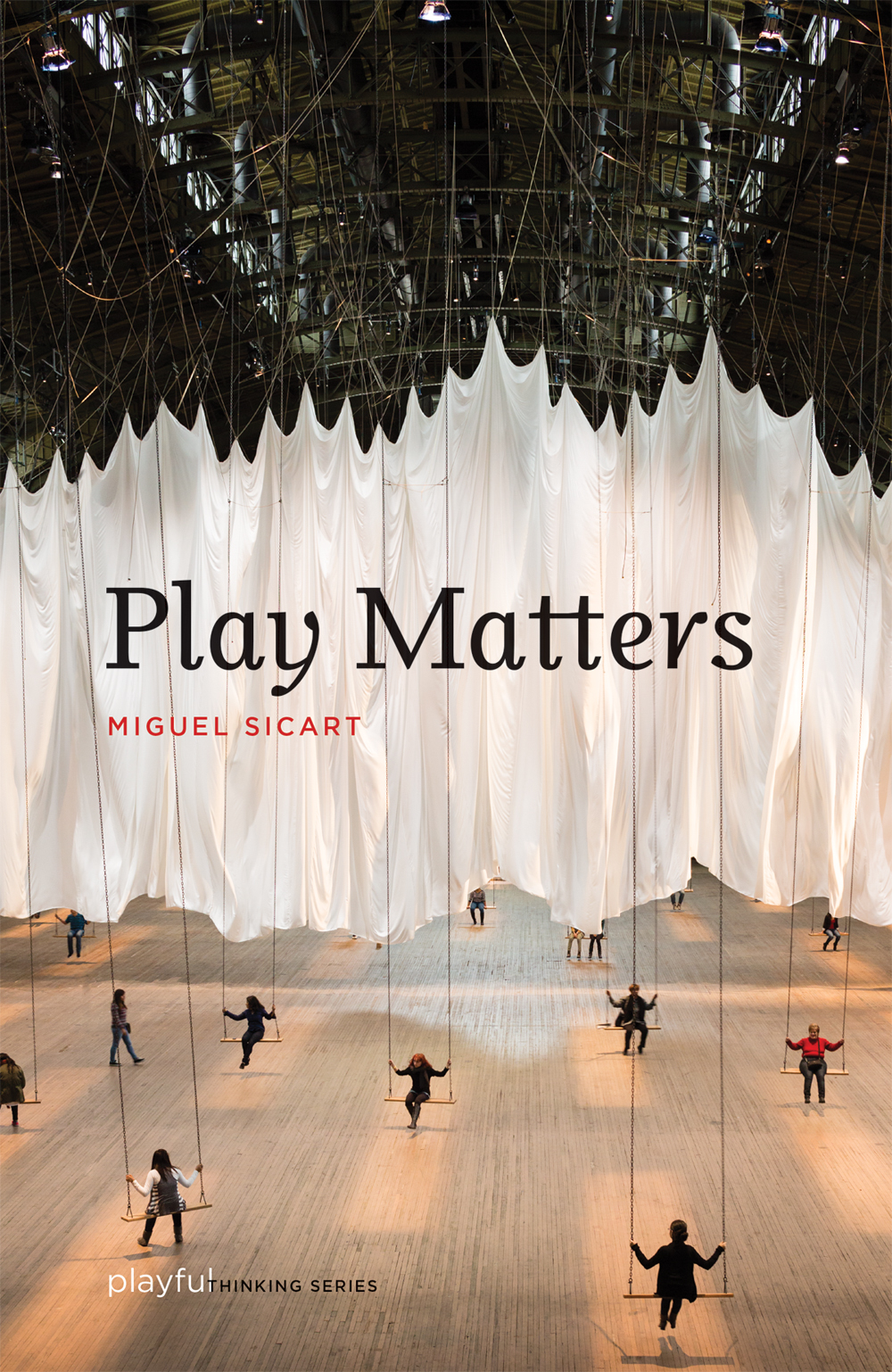

This post features a book review of Miguel Sicart’s Play Matters. Released as part of MIT’s Playful Thinking series, Sicart proposes a reconceptualisation of play as a universal tool for exploring, understanding and producing relations with the world.

Throughout this blog I plan to write around the topics of art, experiential education theory, play, environment design, gallery education and informal learning. This will be done through various forms including discussion of current research, case studies of museums, galleries, libraries and community spaces, topics of currency within the media and reviews from parents and children participating in activities. This post is the first in a series that will review key texts in the field.

Miguel Sicart’s background is in computer gaming theory which I originally thought would be a distinctly different field to mine. How wrong I was. Gaming theorists, such as Sicart, Paolo Pedercini and academics associated with the MIT Game Lab have built the framework of my ‘play’ literature review. I believe this to be the result of three main reasons: 1) they do not perceive play as something that is isolated to childhood AND like me, they are also designers or ‘architects’ of environments in which play emerges. This paves a unique perspective for the creation and conceptualisation of play environments.

A major focus of my doctoral research is about situating play as a methodological approach for children to use to construct meaningful understandings of the world and expressing that through the process of creating art alongside others. Whilst I hold back from making the direct link between Sicart’s writing and my research within this blog, the theoretical paradigm that Sicart presents constructs a framework for understanding children’s experiences with other people, objects, spaces and ideas.

Playful thinking series: Play Matters by Miguel Sicart. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014; Hardcover: £13.95 (176 pp.).

Play Matters presents a new conceptual framework for play as a meaningful experience embedded in reality. This is to say that play is not something that is removed from day to day living but an integral and deep part of it. Sicart advocates for a definition of play as an experience highly dependent upon and responsive to the fixed social structures in which it occurs. The originality of Play Matters lies in its diversion from Johan Huizinga’s heavily cited theories of ‘magic circle’ and ‘man the player’ which locate play within the temporal fantasy world of the user. Huizinga famously claimed that play is a non-serious activity that occurs within a suspended time and place. Whilst both theorists recognise it as an intrinsically motivated and meaningful activity, Sicart departs from Huizinga in his belief that play is a deeply serious activity rooted in reality. He proposes a new paradigm for the theory of play based upon user agency, creativity and expressionism.

The originality of Play Matters lies in its diversion from Johan Huizinga’s heavily cited theories of ‘magic circle’ and ‘man the player’ which locate play within the temporal fantasy world of the user. Huizinga famously claimed that play is a non-serious activity that occurs within a suspended time and place. Whilst both theorists recognise it as an intrinsically motivated and meaningful activity, Sicart departs from Huizinga in his belief that play is a deeply serious activity rooted in reality. He proposes a new paradigm for the theory of play based upon user agency, creativity and expressionism.

Chapter one presents Sicart’s multi-layered conceptual understanding of play. Play is defined as a meaningful exploration and expression of individual thought and feeling. The framework he builds emphasises its transformative potential: ‘through play we experience the world, we construct it and we destroy it, and we explore who we are and what we can say.’ Emphasis is placed upon the relationship between the social, spatial and cultural context in which the activity is occurring. The potential to create ‘carnivalesque’ disruptions to thinking patterns and social norms is discussed in relation to the construction and deconstruction of an individual’s understanding of the world.

Chapter two explores playfulness and its ability to ignite a sense of curiosity about the world in non-play objects and activities. Chapters three and four focus upon the strengths and weaknesses of objects and environments designed to promote specific types of play such as playgrounds, computer games and parks. The conclusion is drawn that whilst these objects and spaces have been designed for particular behaviours to emerge, it is the individual’s intrinsic meaning-making that ultimately determines how these are appropriated and used.

Chapter five explores the ‘beauty’ and ‘artistic’ qualities of play in regards to the production of artworks. Here the critical contemporary art theories of Nicholas Bourriaud and Allan Kaprow are connected to a new paradigm for the creation of art and individual artistic expression that challenges current art world establishments. Sicart not only makes the link between play and the creative process but argues that play is the creative process. Chapter seven explores the ‘architecture’ and ‘forms’ of computer games that provide a starting point for play. Emphasis continues to be placed on its metamorphic capabilities:

‘Play is a powerful manifestation of knowledge and being in the world, a way of becoming, learning, and expressing ourselves that is deeply and inherently human, though never isolated from a world of cultures and materials with which we play, they themselves playing too.’

The chapter concludes with a proposed reconsideration of the title of ‘designers’ of environments to ‘play architects.’ Through this, a new approach is established that emphasises the responsibility to create environments built around the need for users to be able to appropriate, explore and express their understanding of the world through the act of playing.

The book concludes with a deliberation of the role of play within the age of computers. Sicart considers the potential of computers to fuel deep play experiences via their ability to enhance play aesthetics, create new worlds using graphics and sound, connect virtual and real play worlds and bring together play communities. At times the perspective borders on utopianism stating that ‘computers can help play take over the world.’

Play Matters constructs a convincing reconceptualisation of play as a universal tool for exploring, understanding and expressing individual meaning about the world. Play is not something that exists only in childhood, the playground or fantasy. Play lives deeply and willfully in every day reality. Play is a means of connecting people with themselves, with others, with new ideas and constructing divergent ways of thinking. To describe play is to articulate the meaningfulness of the experience to the individual living it. Play is not a luxury; it is a central pillar to personal evolution and one’s ability to live a meaningful life. Therefore play does unquestionably matter.